Having the right data is crucial in running an online business. It supports decision-making with evidence. In my striving for privacy I've been exploring the idea of privacy as core part of online business models. I found that this subject is mostly approached from the consumer's perspective. We have data about privacy violations, from data breaches to unjustly collected data, but not on privacy-friendly practices. And that's a problem.

In business, following the principles of Privacy by Design and by Default means taking extra measures to limit your own data collection. It's a good - and legally required - baseline, requiring organisations to reflect on how they manage personal data. Tenets like data minimalisation means not collecting it unless you absolutely have to, or by giving users a choice if the collection is optional.

But from a business perspective it hampers the ability to collect useful data. Data that in its final form does not violate privacy standards, but that initially needs to be collected on an individual level. With our understanding of privacy being one-sided and biased towards the consumer, we tend to ignore the costs and uncertainty associated with a focus on collecting less data.

Visitor numbers

One of these variables can be observed in the data not collected. We hear a lot about website analytics as problematic data collection, mostly due to the invasiveness of marketing and big tech in this space. The idea of these systems is to not just collect data on a subset of visitors, but on all of them. For the targeted advertising systems to be effective, everyone needs a personalised profile. They're not built to use statistics to make predictions for the whole population, they're built to target every visitor individually.

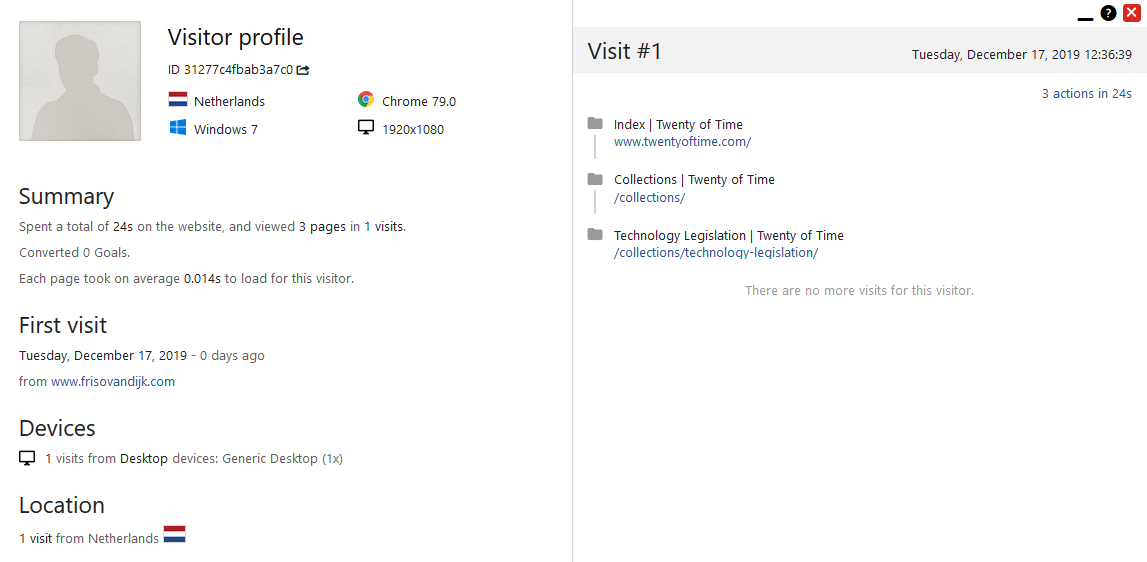

This website uses Matomo, a website analytics tool that I host myself and thus gives me full ownership and control over that data. Even with the most privacy-friendly settings, Matomo creates a somewhat identifiable profile for each user: part of the IP address, browser language, screen resolution, pages visited, and so on. When combined with other data sources, it would allow someone to identify the specific user. While I use that data in aggregated form, such as the total number of visitors on my blog or a specific page, it's still stored as individual records before it gets to that stage.

Following the principles of Privacy by Design and Default within the current legal framework, I've implemented the measure of honouring a Do Not Track (DNT) request. DNT is a browser setting that simply tells a website you don't wish to be tracked. If you visit this site with DNT, the website analytics will not store any data, even though I have the means nor the intention to identify individuals. Storing this data means that the default should honour DNT.

The first cracks in this design appear when we realise that ignoring people with DNT also means that we don't know how many visitors use DNT. No data is collected at all. It means that the available data on the total number of visitors is incomplete. I have two sources to compare my analytics data with: historical data from Google Analytics and anonymous statistics collected by the newsletter widget. Both of them indicate that there are between 20% to 50% more daily visitors to my website than registered through Matomo. While that data is not very accurate, it creates reasonable doubt that there's a non-zero number of visitors that are not being accounted for.

Missing these numbers for identifying screen size and device type is not really an issue. A statistically significant portion of the visitors would be sufficient. The problem is that not having these total numbers makes it impossible to reliably measure some key metrics for my blog, metrics that are used to determine the size of my audience. If I would want to make money from this blog, it would influence the value of sponsorship, marketing efforts and site improvements. Designing for privacy in this case might mean losing out on revenue.

Opting in

2021 edit: The comment system described below has been replaced by a privacy-friendly alternative

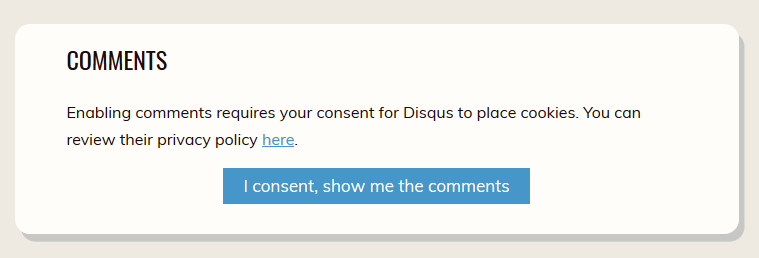

Another privacy measure we hear a lot about is consent, and there we find another set of missing data. Allow me to illustrate this with the comments below each article. I use an external service provider called Disqus to show spam-free comments that easily integrate into a website. Disqus is a notorious tracker, making a small exception for personal websites. Even so, they do place third-party cookies and collect anonymised data, so I chose to hide them under a consent button.

While I was initially proud to implement this feature in a privacy-respecting manner, it turns out that nobody is using them. Ever since I made it consent-based, I've gotten 0 comments through this system. The number of emails with feedback, discussion and follow-ups to my articles have increased, but at the cost of engagement.

Because no data is collected on the number of visitors to the comments, it's an unknown how many people opt in at all. Even if I were to collect some data on the number of users, it would only create further questions of why people didn't opt in. You don't know how many people consciously chose not to opt in instead of ignoring the comments or not knowing they're there.

These issues hold true for all kinds of opt in behaviour. Because consent needs to be specific, narrowing it down to a part of the website like these Disqus comments gives users a clear choice between one-off data collection by a third party and the added value of comments. Even if I were to collect data on the number of people that give their consent, it would be useless when trying to identify the portion of my total audience that decided to opt in. As previously established, the numbers needed for that calculation are inaccurate.

It's data like this that would allow me, as owner of this website, to make choices in how to design for privacy. Maybe a significant enough portion of my audience doesn't use the comments because they choose not to opt in. Maybe they don't even know it exists. Both are problems with different solutions, like switching comment systems as opposed to advertising they're there. Without collecting any data, the choices are shrouded in uncertainty.

Missed purchases

The same argument for missing data can be extrapolated to the broader context of consumer privacy. There's very little data on people who never start or choose to stop using a service because of privacy concerns. The available data comes from online surveys, and self-reporting is known to be an unreliable tool to measure these things. The privacy paradox is a thing, so we know people say they care more about privacy than their behaviour would suggest. It's too unreliable to make a business decision on.

Another source of data is the success of other businesses. Let's use Facebook as an example. Their business practices have not been in the most favourable light in recent years, from fake news to hate groups to privacy issues. In 2018, Facebook reported a lower number of daily U.S. users for the first time ever. This decrease can be attributed to any of the issues surrounding the tech giant: human rights, radicalisation and privacy are just some of them. Any conclusion drawn from this data about privacy concerns could be correct, but will always hold a high degree of uncertainty because we don't know if it's accurate. It could just as easily be that young people leave because it's no longer cool to be on Facebook.

The same occurs in the smart home market. With Amazon and Google leading the race, this is a growing market that comes with a host of privacy concerns. But we do know that it's a shaping up to be a multi-billion dollar market, so perhaps its a good opportunity to launch a privacy-friendly alternative to the tech behemoths' spying. So I'm asking myself what we know about people who choose not to join in because of privacy concerns. How do you collect data on customers who don't like you collecting their data? I've found one survey stating that 28% of people who didn't buy smart home technology did so because of privacy and security concerns, but it's very limited compared to the data available on people who are buying in.

Why it matters

This lack of data makes privacy-oriented business decisions more difficult. Without it, launching a privacy-respecting service or product means taking an additional risk on top of launching a new product. A company would be targeting an audience of an unknown size and will have to find new ways to collect data on the effectiveness of their efforts. The best guess comes from observing how existing privacy-supporting companies fare, and even then we only see the successes.

Investigating this missing data tells a story, this one of the nuances in tackling the issue of privacy. The status quo has created a data-driven narrative that we cannot abolish without second thought. Deciding not to collect personal data means shooting yourself in the foot. Even a small website like mine can feel the effects of making that choice.

Innovative companies are showing up everywhere to solve these issues. They're taking that risk, betting on their believe in the right to privacy. They recognise that the likes of Google started as just a search engine, only going down the wrong path when needing a business model. If the new kids on the block can find enough support, not just to survive, but to thrive and claim a meaningful place in their fields, it may influence the decisions made by the rest. Until then, I fear we're stuck with the status quo. Privacy isn't free, and investing in it right now is a business risk.